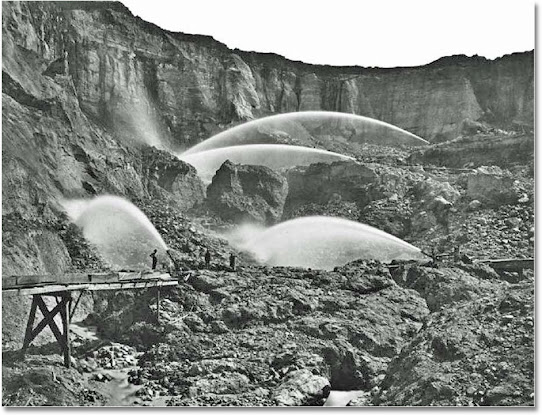

A paper written by one of my graduate students, Christina Tipp, has provided strong evidence that large swaths of the northern Sierra Nevada were completely buried by river sediments in the Eocene, ~30-40 million years ago. This study, published in the American Journal of Science, presents our first glimpse of the northern Sierran landscape in the Eocene and early Oligocene. Known as the 'auriferous gravels' or the 'Tertiary gravels,' these ancient fluvial sediments contained gold that was sought after by miners during California's Gold Rush. At the peak of the Gold Rush, the loosely cemented deposits were blasted by water cannons known as monitors and funneled into sluice boxes to recover the gold in a process called hydraulic mining.

Hydraulic mining at the Malakoff Diggings, just north of the South Yuba River. The cliffs in the image are composed of ~40 million year old river deposits. Note people in the lower left of the image for scale. Photo credit: University of California.

Because of their economic importance, the auriferous gravels were mapped and described in great detail. Waldemar Lindgren, a geologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, oversaw much of this work and compiled it in his 1911 masterpiece, The Tertiary Gravels of the Sierra Nevada of California.

A snippet from the 1900 Colfax Economic Geology map produced by Waldemar Lindgren. The auriferous gravels are shown in red. The image represents an area ~15 km wide.

It's important to realize that the auriferous gravels shown above (in red) are just what's left of the original deposits after tens of millions of years of erosion. By carefully examining geologic maps and analyzing the locations of the remaining deposits with respect to the surrounding topography, Christina was able to reconstruct the original extent of the deposits using basic geometric relationships. For example, if remnants of the auriferous gravels can be found on one side of a valley, then, originally, they were likely also on the other side of the valley.

Topographic cross-section showing gravel remnants in red and the reconstructed gravel deposit in grey. Because auriferous gravels can still be found along the northern slope of the wide valley, as well as along the valley floor, they must have completely filled the valley in the past.

The stunning result from this painstaking work is a map showing that large areas of the northern Sierra Nevada were once buried under at least 200 cubic kilometers of fluvial sediments that were at least 400 m deep at some locations. This means that if we travelled back in time 30-40 million years, we would see large braided rivers flowing down the western slope of the range across wide plains composed of sand and gravel.

Map of the original extent of the ancient auriferous gravels (shown in yellow) - click on the image for a more detailed version. Note that this is conservative reconstruction. For example, gravels can be found at the top of Spanish Peak and Mt. Claremont, two high points in the Feather River watershed, suggesting that the original deposits were broader and deeper than depicted here.

Comments

Post a Comment